THE POWER OF PSYCHOLOGY IN ORGANISATIONS

- Mind Catalyst

- Jul 27, 2025

- 31 min read

Psychology offers fascinating and useful insights into how homosapiens function and the underlying factors and mechanisms at play that undergird those behaviours. Here, we take a plunge into the riveting world of psychology and see if we can extract any workable, applicable or salutary lessons .. Ready?

Let’s begin with a few truly revolutionary and phenomenally EQ-packed questions first, shall we?

Part 1:

“What do you think we could do?”

OR

“What would be your advice on what we could do?”

Those two questions are (almost) one and the same, and they are brimming with psychological tactics and nuances that are poised to help one achieve their goal, and foster and preserve fraternity, understanding, rapport and maintain goodwill and a positive atmosphere within the team or organisation. Due to 4 main reasons:

Firstly, using the word “we” instead of the more singular subjects “I” or “you”, negates and transcends any potential undercurrents or subliminal misinterpretation. It skips beyond any possibility of a “Me Vs You” impression being made inadvertently. And it sets the stage for maintaining a positive, uplifting, amiable atmosphere as well as promoting goodwill, inclusivity and responsibility within the team/organisation. Inasmuch as, what applies to “me” also applies to “you” or “them”.. And therefore, it implies that “we” are equal and that we are in this together.

Secondly, the use of “could” instead of the more limiting “should” helps open the mind of the other person to new options and possibilities. It is like a mental/cerebral and cognitive can opener. It unlimits people’s thoughts and expands their horizons and thinking processes. It promotes new thoughts and ideas, instead of implicitly and subliminally confining and limiting one’s options, according to research, to just two options. Using “could” allows for finding more and better

“...considering what one could do shifts people from analyzing and weighing what they assume to be fixed and mutually exclusive alternatives to generating options that might reconcile underlying imperatives. Having a ‘could’ mindset helps individuals engage in divergent thinking.

(And) in group contexts, we find that adopting a ‘could’ mindset encouraged individuals to spend more time discussing these dilemmas and generating more ideas.”

The use of “What do you think” and “What would your advice be” insinuates and evinces that the person being asked this question knows something the enquirer doesn’t. This feeds any ego that person (the one being asked) might have, increases pride and promotes interest and thus, increases the likelihood of a keen and enthusiastic response, instead of a desultory or perfunctory one.

The fact that all of this is phrased/posed as a question! And there are 4 sub-points to consider here:

It shows that you value that person

And consequently, that you are willing to listen to them, instead of dismissing them. Listening entails staying silent. After all, the same letters that spell the word “listen” spell the word “silent”. Listening also has another merit up its sleeve: When we listen to the other person, we can then identify, analyse and subsequently decide on their way of thinking, their mindset and thoughts, and we can then use that to adjust and match or attune our thought frequency with theirs, so that we’re in harmony. Another powerful advantage to listening is that it aids greatly in persuasion and negotiation. Inasmuch as when we listen, we’re more likely to ask questions, which means that, instead of laboriously trying to convince the other person of something, we could as well then get the other person to say it themselves, so that we wouldn’t even need to persuade them of anything. We will have, then, persuaded/convinced them of something without having actively done any persuasion or done anything at all! That’s analogous to the old saying “fight without fighting”, or despite being more pertinent to adversarial situations “The art of fighting is to subdue the enemy without fighting”. Now that’s efficacy delivered! In other words, we usually don’t listen to understand, we listen to reply, but what most people ever truly want, the root behind all human desires -including money, power, recognition, being liked/respected, fame etc..- is our innate desire to be understood and heard. That’s what anyone truly wants at a very deep, fundamental psychological level. So, when we listen -and by ‘listen’ I mean listen to understand not listen to reply- we grant ourselves the golden opportunity for persuasion, negotiation and having a deep impact on others.

Therefore, if we’re listening, that evinces that we’re making a conscious and purposeful effort to understand them, to understand where they’re coming from and their rationale, instead of going the expedient route and judging them. By being non-judgmental, we offer the other person a “security blanket”, that they shall not worry or fear, that they can be themselves, and candid with us, that we are simply looking for answers, instead of an opportunity for judging them (or looking for a chink in their armor to exploit in an ad hominem way). A non-judgmental environment makes them feel secure, and thereby, promotes mutual trust and goodwill.

Lastly, the mere reality that it is phrased as a question, per se, opens the mind of the person we’re addressing, comparable to what using “could” instead of ”should” does. So it has a compounding effect on it when utilised in conjunction with “could”.

After all, people don’t say that “A statement closes the mind. A question opens the mind” for nothing..

Next, we have another similar phrase posed as a question instead of a statement, which as mentioned hereinbefore, eventuates an open mind that’s attuned to empathic, intelligent and progressive thinking.

“Can I see if I understand?”

“There's a lot of power packed into these six words, and emotionally intelligent people appreciate why.

First, no matter what happens after this sentence, you've signaled to someone else that you care to make the attempt to understand where they're coming from. You're not assuming you understand and you're not ignoring them. You're making the effort.

Second, the fact that it's phrased as a question? Chef's kiss. There's emotional power in asking permission like this, and it likely gives you leeway as you articulate your understanding.

Finally, it's powerful because if you're asking to understand, you're not saying things that are less effective at building rapport; for example, summarily assuming "Look, I know how you feel."

Whether we're talking about people's deep convictions, or their experiences -- or even the details of a supply they need to purchase, or driving directions -- everyone wants to be understood. But, most people also understand how difficult it is to do that, if you truly mean it.”

Moreover, we have a very simple, one-word magical question that is infamous for being asked so frequently by toddlers ..

“Let’s think about why”

OR

“Why (not)?”

“"Why" is a magic word. It's like a linguistic can opener that pries motivations free, and separates emotion from objectivity.

-"Why are we all competing to buy the same product?"

-"Why am I working so hard on this one particular project?"

-"Why am I so quick to respond when this demanding client asks something of me?"

-"Why am I still working late nights and weekends, when my family would rather have me home?"

-"Why is the person in that car yelling at me?"

People who challenge themselves to ask this question over and over, both silently (to themselves) and out loud, are more likely to find the things that they're emotionally motivated to achieve, and to avoid the ones they don't.

And when they find unhealthy emotions acting as the driving forces, they can look elsewhere.”

Part 2: The Findings of Organizational Psychology throughout the decades

Goal Setting in Organisations:

Goal-setting principles according to Locke & Latham’s theory;

Clearly defined with measurable deliverables

Challenging so that achieving the goal(s) feels like a genuine reward

Complex but broken down into doable bite-size objectives to be achieved within set time periods

Commitment to the task, for that the task should be accepted and understood by the goal setter and not someone else.

Positive, constructive, strategy-focused Feedback to track progress

One method of goal-setting predicated upon these 5 principles is the SMART method, which stands for goals that are;

Specific

Measurable

Attainable

Relevant

Timescaled (having a timescale)

Adaptive Leaders:

Heifetz (2009) and Heifetz et al. (1997) define leadership as the 'art of mobilising people (in organisations and communities) to tackle tough issues, adapt and thrive' (2009). The argument is that leadership itself has to change. Rather than leading by providing solutions, the leader must lead by shifting the responsibility for change to the workforce.

Heifetz et al. (2009) offer six key principles of adaptive leadership and these are as follows:

'Get on the balcony'. An adaptive leader needs to see the whole picture and to view the organisation and the way it works as if they were observing from above.

Identify the adaptive change. An adaptive leader needs to not only identify the need for change but be able to determine the nature and extent of the change required, be that to organisational structure, values, working practices or working relationships.

Regulate distress. Adaptive change will both stress and distress those who are experiencing it. This cannot be avoided but it can be managed. The pressure needs to be enough to motivate people to change but not so much that it overwhelms them. The

adaptive leader needs to be able to tolerate the uncertainty and frustration and to communicate confidence.

Maintain disciplined attention. An adaptive leader must be open to contrasting points of view. Rather than avoiding or covering up issues that are difficult or disturbing, they must confront the issues directly.

Give the work back to the people. An adaptive leader must recognise that everyone in the organisation has special access to information that comes only from their experiences in their particular role. Adaptive leaders must step back from the traditional role of telling people what to do and, by allowing them to use their special knowledge, recognise that they are best placed to identify the solutions to the problems.

Protect voices of leadership from below. Heifetz et al. argue that 'giving a voice to all people is the foundation of an organisation that is willing to experiment and learn'. In many organisations, those who speak up are silenced. An adaptive leader needs to listen to these voices to learn of impending challenges. Ignoring them can be fatal for the organisation.

Self-determination theory

Self-determination is a theory of motivation and personality that is based on the assumption that human behaviour is motivated by an innate need for growth and improvement.

Deci and Ryan (1985) first used the term 'self-determination' in their 1985 book Self-Determination and Intrinsic Motivation in Human Behavior. They identify the following innate psychological needs that are essential to self-determination and well-being:

Competence: this is the need to effectively deal with our surroundings. Competence is possessed by a person who has sufficient knowledge or skills to complete a task, interact effectively within their environment, and achieve their goals. Positive feedback, e.g. recognition, can enhance competence, but negative feedback or undertaking a task that is too challenging can undermine feelings of competence.

Relatedness: the need to belong to a group or be close to others. This is possessed by a person who feels a sense of belonging or closeness to other people. Relatedness helps the person access support to achieve goals and is enhanced when the person feels wanted in a group. Conflict with or exclusion from groups can reduce relatedness.

Autonomy: the ability to feel independent and in control of one's choices. Autonomy is possessed by a person who feels in control of their choices and their future. Being given freedom to monitor and manage their own behaviour enhances autonomy; being controlled or coerced reduces autonomy.

Leadership Styles Behaviours:

Muczyk and Reimann (1987) argue that democratic leadership may not always be the most effective and that it may be harmful in some situations. They argue that 'leadership is a two-way street, so a democratic style will be effective only if followers are both willing and able to participate actively in the decision-making process. If they are not, the leader cannot be democratic without also being 'directive' and following up very closely to see that directives are being carried out properly'.

In this quote, Muczyk and Riemann are emphasising the difference between 'participation' and 'direction:

They view direction as a separate dimension of leadership and one that could work in conjunction with participation. This means that as well as the democratic/autocratic distinction, there are two further leadership factors that need to be considered:

• Participation: low participation would be an autocratic leader and high participation would be a democratic or participative leader.

• Direction: low direction would be permissive with little or only general supervision and high would be directive, with close supervision and constant follow-up.

The 3P model of Leadership

James Scouller published a Book in 2011 wherein he posited his treble-layered theory of integrated leadership. This theory is sometimes referred to as the 3P model of leadership due to the three key elements.

• Public leadership: these are the behaviours required to influence groups of people. The public level is an 'outer' level of leadership; it deals with group building and trust.

• Private leadership: these are the behaviours involved in influencing individuals. This can involve getting to know individuals within a team and agreeing individual goals that contribute towards group aims. This is also an 'outer' level of leadership as it deals with coaching, managing and even removing individual members from a group.

• Personal leadership: these are the leadership qualities shown by the individual. It relates to the psychological and ethical development of a leader, as well as their technical ability. It includes the skills and beliefs of a leader: their emotions, subconscious behaviours and their 'presence'. Scouller argued that leaders need to 'grow their leadership presence, know-how and skill' through developing their technical know-how and skill, demonstrating the right attitude towards other people and working on psychological self-mastery. This final aspect is the most crucial aspect of developing a leadership presence.

Leadership Practices Inventory

and Posner developed back in 1987 the Leadership Practices Inventory (LPI) to measure the extent to which an individual engages in each of the five practices of exemplary leadership that they established through their research with successful leaders. These include modelling desired behaviours, inspiring others, challenging the accepted practices, enabling others and encouraging and rewarding others.

Five leadership practices

1. Model the way

'sets a personal example of what he/she expects of others'

'is clear about his/her personal philosophy of leadership'

2. Inspire a shared vision

'describes a compelling image of what our future could be like

'appeals to others to share an exciting dream of the future'

3. Challenge the process

'experiments and takes risks even when there is a chance of failure'

'challenges people to try out new and innovative ways to do their work'

4. Enable others to act

'Treats others with dignity and respect'

'Supports the decisions that people make on their own'

5. Encourage the heart

'Praises people for a job well done.

'Makes it a point to let people know about his/her confidence in their abilities'

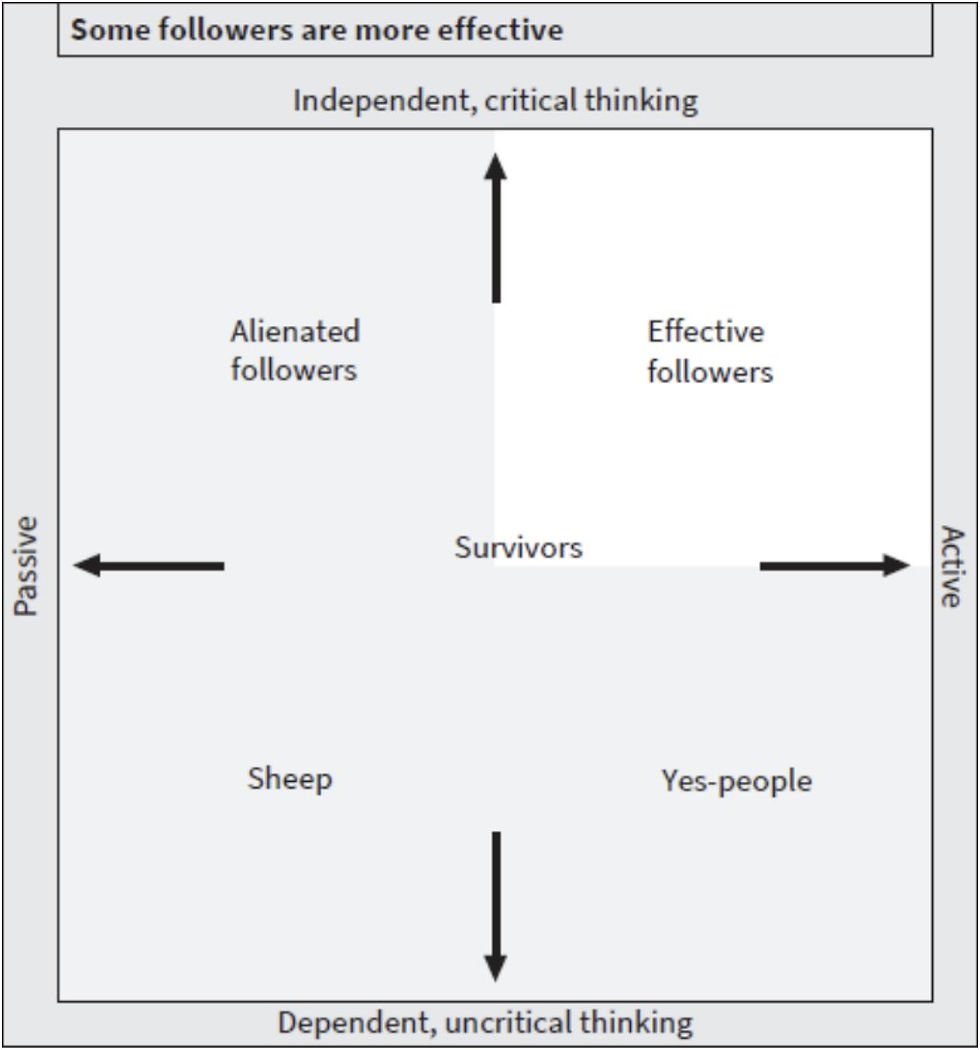

Kelley’s Followership Theory

It is important to recognise that the role of leader can only be understood by also examining the reciprocal role of follower: Kelley (1988) claims that the study of 'followership' will lead to a better understanding of leadership. The success or failure of a group may not be solely down to the ability of a leader but may also be dependent on how well the followers can follow.

Kelley identified two dimensions that help explain followership.

The first dimension is independent critical thinking; wherein individuals are more or less inquisitive and questioning about what is going on around them.

The second dimension is whether the individual is active or passive; Passive behaviour is where followers step back and wait for others to act whereas active followers are motivated to act to meet organisational goals if they see the opportunity.

This gives us five styles of followers, described as follows:

The sheep: these individuals are passive, lack commitment and require external motivation and constant supervision from the leader. Sheep perform a task they have been given and then stop; they do not use initiative or critical thinking.

The yes-people: these individuals are committed to the leader and the goal (or task) of the organisation (or group/team). These conformist individuals do not question the decisions or actions of the leader. Further, yes-people will defend their leader when faced with opposition from others.

The survivors: these individuals are not trail-blazers; they will not stand behind controversial or unique ideas until most people in the group have expressed their support. These individuals go with the flow and survive changes within the organisation well.

The alienated followers: these individuals are negative and critical as they question the decisions and actions of the leader. However, they do not often voice such criticism and are fairly passive in carrying out their role.

The effective followers: these exemplary individuals are positive, active and independent thinkers. Effective followers will not unquestioningly accept the decisions or actions of a leader until they have evaluated them completely. Furthermore, these types of follower can succeed without the presence of a leader.

Kelley also described four main qualities of effective followers:

Self-management: the ability to think critically, work independently and control one's actions. Followers must be able to manage themselves well for leaders to delegate tasks to these individuals.

Commitment: an individual's dedication to the goal, vision or cause of a group or organisation. This quality helps keep the follower's morale and energy levels high.

Competence: possessing the skills and aptitudes necessary to complete the goal or task for the group or organisation. Individuals with this quality often hold skills higher than their average co-worker and pursue knowledge by upgrading their skills (e.g. through further education or training).

Courage: maintaining one's beliefs and upholding ethical standards, even in the face of dishonest or corrupt leaders. These individuals are loyal, honest and open with their leaders.

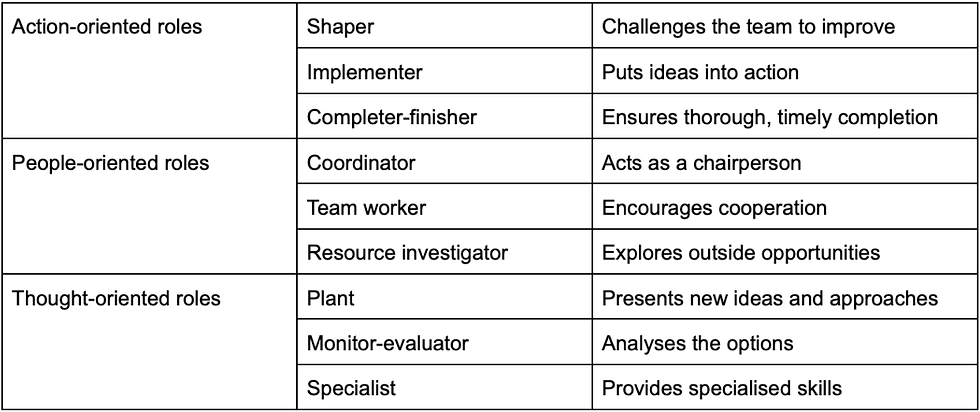

Belbin's Theory of Team Roles (1981)

Belbin proposes that an ideal team contains people who are prepared to take on different roles.

Action-oriented roles:

The shapers: people who challenge the team to improve. They are dynamic and usually extroverted people who enjoy stimulating others, questioning established views and finding the best approaches for solving problems. Shapers tend to see obstacles as exciting challenges, although they may also be argumentative and upset colleagues.

The implementers; the people who get things done. They turn the team's ideas and concepts into practical actions and plans. They tend to be people who work systematically and efficiently and are very well organised. However, they can be inflexible and resistant to change.

The completer-finishers: These people ensure that projects are completed thoroughly without mistakes with close attention to the smallest of details. Completer-finishers are concerned with deadlines and will push the team to make sure the job is completed on time.

They are described as perfectionists and may worry unnecessarily and find it hard to delegate.

People-oriented roles:

The coordinators: those individuals who take on the traditional team-leader role and guide the team to the objectives. They are often excellent listeners, recognising the value of each team member. They are calm and good-natured, and delegate tasks very effectively. Coordinators, however, may delegate too much personal responsibility, and can be manipulative.

The team workers in contrast, are the people who provide support and make sure that people within the team are working together effectively.

These people are negotiators and are flexible, diplomatic and perceptive. These tend to be popular people who prioritise team cohesion and help people get along but can also be indecisive and struggle to commit.

The resource investigators are innovative and curious. They explore the available options, develop contacts and negotiate for resources on behalf of the team. They are enthusiastic team members, who identify and work with external stakeholders to help the team accomplish its objective. Resource investigators are outgoing and people are generally positive towards them. However, they may lose enthusiasm quickly.

Thought-oriented roles:

The plant: this is the creative person who comes up with new ideas. They thrive on praise but struggle to take criticism. Plants are often introverted and prefer to work on their own; their ideas can sometimes be impractical and they may also be poor communicators.

The Monitor-evaluators on the other hand, are good at analysing and evaluating the ideas that other people propose. They are smart, objective and strategic and weigh the pros and cons of different options before coming to a decision, but can be seen as detached or unemotional.

The specialists are people who have specialised knowledge that is needed to get the job done. They pride themselves on their skills and expertise but may sometimes focus on technicalities at the expense of the bigger picture.

The significance of clear, lucid, unambiguous communication:

There’s a happy medium between nuance and efficient communication - how to you grab people’s attention without losing important context?

On one hand, brevity ensures that we listen and don't bore the other side to death.

“It takes more time to think about all of [the various aspects, elements and angles of the message] and to craft the right [one]. You might even need to segment things better, so that you don't try to communicate everything to everyone at once. On top of all of that, you have the challenge of being brief. But, when done right, you also get the benefit of being far more likely to achieve your ultimate goals. ... silence speaks volumes. Taking time to weed out the many things you might want to say (because you're thinking emotionally) to make the ones that you truly need to say more memorable, makes the difference between confusion and clarity.”

But, on the other hand, there is a very strong and cogent case to be made for favouring nuance over in-depth communication, and surprisingly, it turns out that nuanced communication is not always necessarily 'inefficient'. Clear, unequivocal communication is essential to avoiding misunderstandings.

"Leaders must provide clear guidance all the time: It's perhaps their most important responsibility. Their troops are only as effective as the clarity of tactical objectives and strategic goals. Employees already face many unknowns in the pandemic recession, and leaders should not compound the problem by exacerbating the fog of war.

When you communicate, use simple and clear language that cannot be misconstrued or misinterpreted. A message should be understood by the entire audience, or a leader isn't doing his/her job."

“Nobody likes homework, but sorry, this is homework before you begin the conversation. It falls into the category of "things that seem self-explanatory and that everyone would know to do, but aren't. Emotionally intelligent people understand that persuasion involves making requests, and that the odds of those requests being accepted depend on knowing how to articulate them effectively.”

“a big error that many promising leaders make: letting their emotions dictate decisions, without realizing how they're undermining their power in the process.”

“Be careful not to let emotional reactions dictate your practical reactions (as opposed to reasoned, thoughtful actions), and be aware of emotional messages you might communicate to the people you lead (intended or not), along with your actual, practical guidance.”

"It's not enough to think we know. To save time, we need to know we know. The core culprit of lost time is miscommunication. This miscommunication often lies within not what is said, but in what isn't said-and the assumptions that follow. In other words, it's very easy to assume the obvious, but that doesn't mean assumptions are accurate.

When managers are already strapped for time, it may feel arduous-if not elementary to explain your desired outcome. After all, if you provide the assignment to an employee, and they don't ask questions it must be because they understand what you're looking for. But people often don't ask questions out of a fear of looking stupid as if they don't already know something they feel they're supposed to.

The onus isn't limited to staff asking questions. It is also on the manager -who can leverage it to intuitively save staff time- which also effectively increases productivity.

What managers can see with the 'two-second rule' is simple: don't assume others will know exactly what you're looking for."

Faulty Decision-making

When a group makes decisions that cause a poor outcome, the underlying reasoning for such decisions is described as being ‘faulty’. Groupthink is an example of that type of faulty reasoning.

Groupthink is a psychological phenomenon that occurs within a group of people, in which the desire for harmony or conformity in the group results in an irrational or dysfunctional decision-making outcome. In other words, the group creates a situation in which a decision is made that would not have been made by individuals.

Janis back in 1971, identified eight different features or symptoms that indicate groupthink, these are:

Illusions of invulnerability. This means that members of the group believe that they can do no wrong and can never be in any sort of trouble. This can lead to overly optimistic thinking about likely outcomes and encourages risky decision-making.

Unquestioned beliefs. A lack of questioning, particularly from a legal or moral standpoint, can prevent group members from considering all the possible consequences of their decisions.

Rationalising. This is where group members ignore warning signs and assume that everything will be alright.

Stereotyping. Group decision-making can involve stereotypical views of those who raise issues or point out problems. This can mean that they are ignored or labelled as members of an 'out-group'

Self-censorship. In a group situation we are less likely to listen to our own doubts or misgivings as it appears to us that no one else has any doubts or misgivings. This is a little like the 'diffusion of responsibility' seen in bystanders to an accident when they assume that, since no one else is responding, that there is no real emergency (see Section 5.2 on the study by Piliavin et al.). In this way, everyone is convinced that there is nothing to worry about.

Mind guards. Janis described these as 'self-appointed censors to hide problematic information from the group'. We don't want the rest of the group to see that we are worried and so we hide this. Unfortunately, if everyone is feeling the same way and hiding their feelings, this can lead to some very risky decisions.

Illusions of unanimity. Groups behaving in the ways that we have just considered will produce the illusion of being unanimous or agreement.

Direct pressure to conform. Groups can place dissenters (those who disagree) or those who question under a great deal of pressure, in some cases making them appear as though they are being disloyal or traitorous by asking questions.

Groupthink can usually lead to extremely poor decision-making. But it can also be a double-edged sword, especially when working with a large number of people, as it often allows the group to make decisions, complete tasks and finish projects efficiently.

The factors that may increase the chances of groupthink include situations where group members are very similar to one another, and that is boosted in the presence of an extremely charismatic leader. High levels of stress or situations that are morally challenging may also be causative factors for groupthink.

The risk of groupthink occurring may be reduced by having the leader allow group members the opportunity to express their own ideas or argue against ideas that have already been proposed. Breaking up members into smaller independent teams can be helpful in achieving this. The leader should avoid stating their views too forcefully, especially at the start of the discussion, so as to not bias or sway anyone’s sentiment and preserve everyone’s authentic and unadulterated feelings and ideas, so that everyone is able to develop their own viewpoints first.

One possibility is that someone gets instructed to deliberately present the opposing view regardless of their own personal viewpoints, reducing the likelihood of groupthink occurring and encouraging the group members to take a critical perspective.

Forsyth’s Three Sins

Cognitive biases, limitations and errors can often affect group decision-making adversely. Forsyth suggests that there are three types of potential bias that may affect group decision-making. He describes each of these as 'sins', meaning a mistake in a non-religious sense.

1. 'Sins of Commission':

This refers to the misuse of information in the decision-making process. There are a number of different sub-types of the Sin of Commission;

Belief perseverance: The use of information in the decision-making process that has already been shown to be inaccurate .

Sunken Cost bias: When group members remain committed to a plan because some investment of time or money has already been made, even though this plan may now be obviously flawed.

Extra-evidentiary bias: If a group chooses to use information despite having been told to ignore it.

Hindsight bias: Falsely overestimating the importance of past knowledge or experience.

2. 'Sins of Omission':

This refers to overlooking key information;

Base Rate bias: unintentionally ignoring very basic relevant information.

Fundamental Attribution error: when members of a group make decisions based on inaccurate appraisals of an individual's behaviour.

3. 'Sins of Imprecision':

This involves relying too heavily on biases and heuristics that over-simplify complex decisions.

The Availability heuristic: over-reliance on the information that is most easily and readily available.

The Conjunctive bias: failing to consider relationships between events.

The representativeness heuristic: where group members rely too heavily on decision-making factors that may appear meaningful but are actually just misleading.

Theories of Individual & Group Performance

The two main assumptions of the social approach to Psychology are:

Our behaviour, cognitions and emotions can be influenced by the actual, implied or imagined presence of others.

All of our behaviour, cognitions and emotions can be influenced by social contexts and social environments.

Social Facilitation:

This is when there is improved performance in the presence of others.

The type of task people undertake can affect their performance. This means that the presence of others does not always lead to facilitation. When people are attempting new or difficult tasks, their performance may be worsened by the presence of others. This is what causes that feeling of not wanting to be watched doing something for the first time, and it is known as social inhibition. In contrast, social facilitation is most readily observed when individuals are performing a task with which they are familiar or find easy.

Social Loafing:

Social loafing occurs when people do not work as hard in the presence of others as they do alone. This is more prevalent when people feel that their behaviour is not being closely watched. In other words, the whole is less than the sum of its parts.

The cause of social loafing can be explained through social impact theory (Latané, 1981), which proposes that individuals can be both a source and a target of social influence. This means they can either exert social pressure over others or be subject to social pressure themselves. Latané treats this theory as a kind of social law that has three rules of social impact.

Social impact theory therefore suggests that when individuals work together, social influence can be diffused across all the group members in the team. If there is insufficient supervision from a manager, the strength, immediacy and number of influencing people is reduced. This means pressure to perform well is significantly reduced, which can cause social loafing.

Conflict Management

Conflict can have significant effects on the physical and psychological health of the people involved, increasing absenteeism and turnover and reducing staff satisfaction. Conflict that constitutes bullying or harassment can have negative effects for

The individuals involved,

The way in which the organisation functions,

The public perception of the company.

There are several types of conflict that can occur in organisational contexts. These include:

Intra-individual conflict: an internal conflict in which the person struggles to make a decision, due to conflicting thoughts or values.

Inter-individual/intra-group conflict: conflict between two or more individuals within a group.

Inter-group conflict: conflict between two groups within the same organisation.

Although there can be numerous causes of conflict within a group, these may be divided into two broad categories: Organisational factors and Interpersonal factors.

1- Organisational factors are issues that are specific to the context of an organisation (e.g. school, workplace, voluntary group). These could be conflict over status or salary, or disagreements over how to achieve a goal. A lack of resources or space can also create conflict.

2- Interpersonal factors may be as simple as a personality clash between two people or that they do not work well together for some reason. If the interpersonal conflict is between leaders of different groups, then this can produce increased conflict very easily.

Conflict handling

Thomas and Kilmann (1974) suggest five modes that can be used to manage group conflict:

• Competition: Individuals may persist in conflict until someone wins and someone loses. At this point, the conflict is over.

• Accommodation: Here, one individual will need to make a sacrifice to reduce the conflict. This can be extremely effective in reducing conflict and preventing further damage to the relationship.

• Compromise: Each group or individual under conflict must make some compromise and give up something to reduce the conflict. This will be effective only if both sides lose comparable things.

• Collaboration: The group has to work together to overcome the conflict.

• Avoidance: Avoidance involves suppressing the conflict or withdrawing from the conflict completely. This does not resolve the conflict, which is still there and has not been addressed. This can be effective in creating a cooling-off period.

The effectiveness of any of the five conflict-handling modes is dependent on the requirements of the specific situation, and also the ability of an individual to effectively use that mode. Using the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) test can help people identify that they rely on some modes more or less than necessary. The overuse or underuse of each mode carries its own risks.

For example, collaborating can help a person creatively combine ideas from people with different perspectives on a problem, but it can also mean work is often delayed due to numerous conversations about the same issue. Overuse of the competing mode can lead other team members being reluctant to speak up about issues that are important to them, but it is a good mode to use when trying to manage a crisis.

Bullying at work

A review article by Einarsen (1999) defines bullying as 'hostile and aggressive behaviour, either physicalor non-physical, directed at one or more colleagues or subordinates'. Bullying causes humiliation, offence and distress and may also affect an individual's work performance and create a negative working environment.

Zapf (cited in Einarsen, 1999) suggests that there are five types of bullying behaviour:

Work-related (such as changing tasks or making them harder to perform)

Physical violence,

Personal attacks (attacks on private life by ridicule, gossip or insulting remarks)

Verbal threats (Ex. humiliation)

Social isolation.

Four phases of bullying are suggested by Einarsen:

• aggressive behaviour

• bullying

• stigmatisation

• severe trauma

Causes of bullying can be divided into two broad areas:

1. Individual or personality factors of the victim and of the bully:

• Competition concerning status and job position

• Envy

• The aggressor being uncertain about their own abilities

2. Psycho-social or situational factors:

• Deficiencies in work design

• Deficiencies in leadership behaviour

• Socially exposed position of the victim

• Low morale in the department.

Einarsen argues that we need to move away from treating all bullying as one phenomenon and that we need to develop an understanding of the very many different types.

Predatory bullying; is where the victim has done nothing to trigger the bullying behaviour, but is 'accidentally' in a situation where a predator is demonstrating power over others. This would be what might be termed 'institutional harassment' where a culture of bullying and aggression is ingrained throughout the organisation.

Scapegoating; is when people are highly stressed or frustrated, and are looking for someone to vent their frustration on. This has also been used as an explanation of prejudice.

In many cases, the organisation effectively tolerates the bullying by not responding appropriately to it or by failing to have the correct policies and procedures in place.

Satisfaction at work

Job Characteristics Theory (Hackman 1976) acts as a framework for analysing how job characteristics affects job satisfaction and other work outcomes. It is a theory that can be used to create jobs that appeal to workers and keep them motivated.

Five key dimensions, described by Hackman and Oldham as core 'job characteristics' are:

Skill variety: a job should require different skills and allow workers to use a range of the skills.

Task identity: a job should require a worker to complete a whole piece of work rather than a single task in isolation.

Task significance: the job should have a worthwhile impact on others, whether inside or outside of the organisation.

Autonomy: the job should allow the worker some freedom in planning, scheduling and carrying out their work.

Feedback: the job itself (rather than other people) should provide information on how well the worker is performing the job, i.e. it is clear that the task has been completed well by looking at the outcome.

These job characteristics are responsible for producing three critical psychological states:

Experienced meaningfulness; the extent to which the employee experiences the work as having a purpose that allows the employee to demonstrate their value to others.

Experienced responsibility; the degree to which the employee feels accountable for their work performance and outcomes.

Knowledge of results; the extent to which the jobholder is aware of how well they are performing their job.

The psychological states mediate the relationship between job characteristics and work-related outcomes such as motivation, satisfaction and work performance.

Absenteeism and organisational commitment

The paper by Blau and Boal (1987) combine the concepts of job involvement and organisational commitment as a way of predicting turnover and absenteeism with their organisational commitment model.

Job involvement is the extent to which a person psychologically identifies with their job.

Organisational commitment is the mental and emotional bond an individual employee has to an organisation.

They produced four possible categories of commitment:

High job involvement and high organisational commitment

Individuals for whom work is important to their self-esteem. Will exert a great deal of time and effort in their jobs.

They identify strongly with the organisation, thus become highly involved with group activities that help to maintain the organisation.

Are most valued members of the organisation, and are likely to get promoted.

Lowest level of turnover and absenteeism.

Are harder to replace, thereby their absence or demission, would have a greater impact on the organisation.

High job involvement and low organisational commitment

Their work is important to them, but do not identify with the organisation or its goals.

Are likely to show high levels of effort for individual tasks but a low level of effort for group tasks.

If the first groups are the 'stars' of the organisation, then this group are the 'lone wolves'.

Are highly sensitive to factors such as working conditions and pay. Would leave if better opportunities were to arise elsewhere

Despite their high levels of individual effort, they do not integrate themselves within the organisation. This can breed resentment if others then need to pick up their group work tasks and perceived inequities can damage the cohesiveness of the group.

More willing to violate absenteeism policies if there is a conflict between a work goal and a personal goal.

Low job involvement and high organisational commitment

Their work is not personally important to them but they do identify with the organisation and its goals.

May exert little effort on individual tasks but a great deal on group maintenance tasks.

Are described as the corporate citizens of the organisation. Their absence can have a significant impact on others.

Low job involvement and low organisational commitment

Work is not viewed as being important to their self-image

Do not put a great deal of effort into individual tasks.

The organisation is not strongly identified with, thus they do not contribute to group maintenance.

These are the least valuable members of an organisation and are described as 'apathetic employees'.

Contingency Theory

The contingency theory views organization design as "a constrained optimization problem". Contingency theory claims there is no best way to organize a corporation, to lead a company, or to make decisions. An organizational, leadership, or decision making style that is effective in some situations, may not be successful in other situations.

Contingency on the organization:

In the contingency theory on the organization, it states that there is no universal or one best way to manage an organization. Secondly, the organizational design and its subsystems must "fit" with the environment and lastly, effective organizations must not only have a proper "fit" with the environment, but also between its subsystems.

Contingency theory of leadership:

In the contingency theory of leadership, the success of the leader is a function of various factors in the form of subordinate, task, and/ or group variables.

The following theories stress using different styles of leadership appropriate to the needs created by different organizational situations. Some of these theories are:

The contingency theory: The contingency model theory, developed by Fred Fiedler, explains that group performance is a result of interaction between the style of the leader and the characteristics of the environment in which the leader works.

The Hersey–Blanchard situational theory: This theory is an extension of Blake and Mouton's Managerial Grid and Reddin's 3-D Management style theory. This model expanded the notion of relationship and task dimensions to leadership and readiness dimensions.

Contingency theory of decision-making:

The effectiveness of a decision procedure depends upon a number of aspects of the situation:

The importance of the decision quality and acceptance.

The amount of relevant information possessed by the leader and subordinates.

The amount of disagreement among subordinates with respect to their alternatives

The Situational Leadership Model

Situational Leadership, developed by Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard, emerged as one of a related group of two-factor theories of leadership, many of which originated in research done at Ohio State University in the 1960s.

These two-factor theories hold that possibilities in leadership style are composed of combinations of two main variables: task behavior and relationship behavior. Various terms are used to describe these two concepts, such as initiating structure or direction for task behavior and consideration or socioemotional support for relationship behavior.

Development levels:

Blanchard's situational leadership II model uses the terms "competence" (ability, knowledge, and skill) and "commitment" (confidence and motivation) to describe different levels of development.

According to Ken Blanchard, "Four combinations of competence and commitment make up what we call 'development level.'"

D1 – Enthusiastic Beginner: Low competence with high commitment

D2 – Disillusioned Learner: Low/middling competence with low commitment

D3 – Capable but Cautious Performer: High competence with low/variable commitment

D4 – Self-reliant Achiever: High competence with high commitment

In order to make an effective cycle, a leader needs to motivate followers properly by adjusting their leadership style to the development level of the person. Blanchard postulates that Enthusiastic Beginners (D1) need a Directing leadership style while Disillusioned Learners (D2) require a Coaching style. He suggests that Capable but Cautious Performers (D3) respond best to a Supporting leadership style and Self-reliant Achievers need leaders who offer a Delegating style.

Furthermore, Blanchard views development as a process as the individual moves from developing to developed, in this viewpoint it is still incumbent upon the leader to diagnose development level and then use the appropriate leadership style which can vary based on each task, goal, or assignment.

The Matching Principle

Successful communication requires recognizing what kind of conversation is occurring and then matching each other. We often struggle with communicating with one another. At times, we may feel unheard by the other person. According to the latest research in neurology and psychology, a discussion doesn't consist of one single conversation, but rather contains many different conversations. And there are three types of conversations:

Practical Conversations:

Conversations where one is seeking advice. It is also called a “What’s this really about?” type of conversation.

Emotional Conversations:

This is when a person is simply seeking empathy from the other side. They do not necessarily want or need advice to solve the problem in question, just for the other side to empathize.

Social Conversations:

These are conversations concerning our social identities and who we relate to each other and to society.

According to the researchers, if two or more people are having different types of conversations at the same moment, they would not be able to connect or hear each other. This is when we’re talking but not communicating with each other.

Another way of thinking of it is asking the other person if they wish to be:

• helped -the practical “what’s this really about?” type of conversation-;

• hugged -which is the emotional “how do we feel?” type-;

or

• heard - a more social “who are we?” conversation.

So, how do we figure out which questions to ask?

The answer lies in asking deep questions. Those are the questions that do not just seek to uncover what happened in another person’s life, but how it made them feel.

For example “instead of asking “Where do you work?”, we may ask a deeper question by inquiring “What do you love most about your work?” or “What’s the most tiring or exciting part of your job?”

By asking deep questions, we allow the other person (and ourselves, when we reciprocate) to be vulnerable and say things that are real, that have depth and texture. It helps us humanize the other person and reveal in context their true wishes and needs. We connect best and deepest with others when there is reciprocal vulnerability at play.

Part 3: Biases, motivations, effects and heuristics

“When the first idea that comes to mind, triggered by familiar features of a problem, prevents a better solution from being found.”

“The tendency to avoid dangerous or negative information by closing yourself off from that information.”

Social Desirability bias

Giving answers to questions that would be more acceptable to society, so as to put oneself in the best light.

Believing one knows something they don’t. Overestimating one’s knowledge and capabilities.

“The tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one's prior beliefs or values. Such as selecting information that supports our views, ignoring contrary information, or when we interpret ambiguous evidence as supporting our existing attitudes.”

ByStander Effect:

“Bystanders who believe that there are other people witnessing an emergency, such as over-hearing someone having an epileptic seizure, are significantly less likely to help than those who believe they were alone in hearing the event. The explanation underlying it is known as the 'diffusion of responsibility' hypothesis, in which an individual person's perceived obligation to help in a situation is reduced when other people are present. Alternatively, if we witness those around us assisting or 'modelling' helping behaviour, we may be more likely to imitate and engage in helping.”

Introduced by Psychologist Leon Festinger in 1954, social comparison theory suggests that people value their own personal and social worth by assessing how they compare to others. Festinger believed that we engage in this comparison process as a way of establishing a benchmark by which we can make accurate evaluations of ourselves.

“The social comparison process involves people coming to know themselves by evaluating their own attitudes, abilities, and traits in comparison with others. In most cases, we try to compare ourselves to those in our peer group or with whom we are similar.”

Greater reliance on information encountered early in a series.

When a disagreement becomes more extreme even though the different parties are exposed to the same evidence.

"The affect heuristic simplifies our lives by creating a world that is much tidier than reality," The eminent Psychologist Daniel Kahneman, framed it as follows; "Good technologies have few costs in the imaginary world we inhabit, bad technologies have no benefits, and all decisions are easy. In the real world, of course, we often face painful tradeoffs between benefits and costs."

“[People] assess the likelihood of risks by asking how readily examples come to mind.

If people can easily think of relevant examples, they are far more likely to be frightened and concerned than if they cannot. A risk that is familiar, like that associated with terrorism in the aftermath of 9/11, will be seen as more serious than a risk that is less familiar, like that associated with sunbathing or hotter summers. Homicides are more available than suicides, and so people tend to believe, wrongly, that more people die from homicides.”

“The availability heuristic allows individuals to judge the probability of an event by the ease with which they can imagine that event or retrieve instances of it from memory.”

“The fluency heuristic refers to the tendency to think something is true just because it is familiar. This heuristic may be especially powerful today, with social media allowing for widespread repetition of the same information. The fluency heuristic may in some cases outweigh the influence of warnings and prompts and dilute their effectiveness at stemming the spread of misinformation.”

“Studies show that negative events in our lives -like criticism or loss- hurt more than positive events make us feel good. We tend to remember bad days more than good days, and traumatic memories cause more psychological harm than happy memories cause joy.”

“When small groups are involved in coming up with solutions themselves, they experience the endowment effect: when we own something (even an idea), we tend to value it more.”

“Humans are more likely to change behaviour when challenges are framed positively, instead of negatively. In other words, how we communicate about climate change influences how we respond. People are more likely to act in relation to a positive frame (“a clean energy future will save X number of lives”) versus a negative statement (“we’re going to go extinct due to climate change”).”

Original Date of Writing: 16/10/2024

Comments